A pirate, a witch, and a lot of fun: *From the Heart of the Wreck* at Cape Rep

Cape Rep Theatre has a tradition of staging geographically and culturally relevant plays—plays about the fishing industry, plays about Cape Cod history—and its world premiere of From the Heart of the Wreck adds a new star to that firmament.

The story itself is well known. In 1984 Barry Clifford discovered the remains of the pirate galley Whydah, the newly acquired flagship of “Black Sam” Bellamy, sunk off Cape Cod in a hurricane in 1717. On its way from the Caribbean to hide its loot in Canada, the fleet had lingered in these dangerous waters because of Maria Hallett, with whom Bellamy was in love. With Bellamy dead, Hallett roamed the backshores, moaning; some say she haunts them still.

It’s a story that—in its many versions—seized the imagination of playwrights/performers Nick Nudler and Kirsten Peacock when Cape Rep asked them to conceptualize an original play for the theater, and that’s precisely the way the play is staged—to leave as much room for conjecture as for facts, to understand that history always has more than one teller, and that there’s generally more to any story than what meets the eye.

The way they do it? Through a short play that’s filled with action, humor, tragedy, music, and amazing ensemble acting.

Three sailors/storytellers—Coleman Churchill, BT Hayes, and Cape Rep’s own Ari Lew—literally and figuratively set the stage as they show how Bellamy and Hallett met at Higgins Tavern in Eastham. Hallet (Peacock) is a woman of “uncertain name and questionable birth” who is “as wild as the Nauset winds” and immediately captures the heart of the handsome Bellamy (Nudler).

Needing the wherewithal to settle down, Bellamy joins up with an English captain sailing for Nassau, the “pirate’s republic,” but the crew tires of the captain’s refusal to attack British ships, and Bellamy is elected to lead in his stead. The storytellers move the tale smoothly though the history—including Bellamy’s famous refusal to use violence when capturing gold-laden vessels, and the role of the triangular Atlantic slave trade of which the Whydah was a flagship—through two years of piracy.

Hallett, meanwhile, is having a rough time of things back on Cape Cod. She settles in a shack in the dunes where she gives birth to a child who subsequently dies; it’s unclear how, though the storytellers admit that “there is no version of the story where the baby survives.” She’s alternately shunned and persecuted by the Puritan locals, escaping death at their hands but condemned to solitude. Convinced Bellamy will return, she prowls the beaches, waiting.

He does return, of course, his ship lashed against the Cape’s treacherous sandbars, and the Whydah comes to rest in the grave of the Atlantic; Hallett sees him die and haunts the area forever after, known to all as the Witch of Wellfleet.

Or not. The storytellers themselves seem to be divided on this point; they have different versions up their collective sleeves. “So which one happened?” asks one of them, to which another responds, “there are many ways to tell the story.”

And that’s precisely how the cast bring this story—or stories—to life. Stepping neatly in and out of their various roles, Lew, Hayes, and Churchill go from unison to individual speaking, from exquisitely choreographed dances to slapstick physical humor, from songs to silence, and each rendition of what could have happened is more engaging than the last. This is ensemble work at its best.

Nudler and Peacock are both brilliant in the roles they’ve created, directed, and strikingly inhabit, though it never feels that they’re stealing the show—to the contrary, it’s a real ensemble piece and one can sense the collaboration happening onstage; there’s a rather exciting feeling that one could attend the play more than once and it wouldn’t be precisely the same, that it’s constantly alive, constantly in the process of evolving.

And in the process, the stage fairly buzzes with energy. It’s worth remembering that Sam Bellamy was only 28 when he died, and this young cast brings that fact physically home to Cape audiences (that generally tend toward the grayscale). They dance, they move with grace and fluidity, they perform feats of gymnastics and intense physical movements, and all with an enthusiasm that’s infectious.

Ryan McGettigan’s stage design complements the play and never intrudes upon it; the scenery is beautiful while being wholly utilitarian. It doesn’t impose anything on either the audience or the actors, but rather seems to fit itself to the action rather than the other way around. A scrim in the back is used to particular advantage to illustrate, insinuate, explain, and more; ropes are far from a mere nautical prop and become alive with multiple uses.

After a wild tour of love, fate, loss, and madness, the ending is beautiful—I won’t give it away, but I will say that people in the audience literally physically leaned into the final monologue. You will, too. It’s entrancing in all the meanings of the word.

This wreck does indeed have a heart, and it’s gorgeous. Highly recommended.

Photos courtesy of Bob Tucker/Focalpoint Studio.

More Recent Provincetown News

Accommodations

Accommodations  Art

Art  Bars

Bars  Books

Books  Entertainment

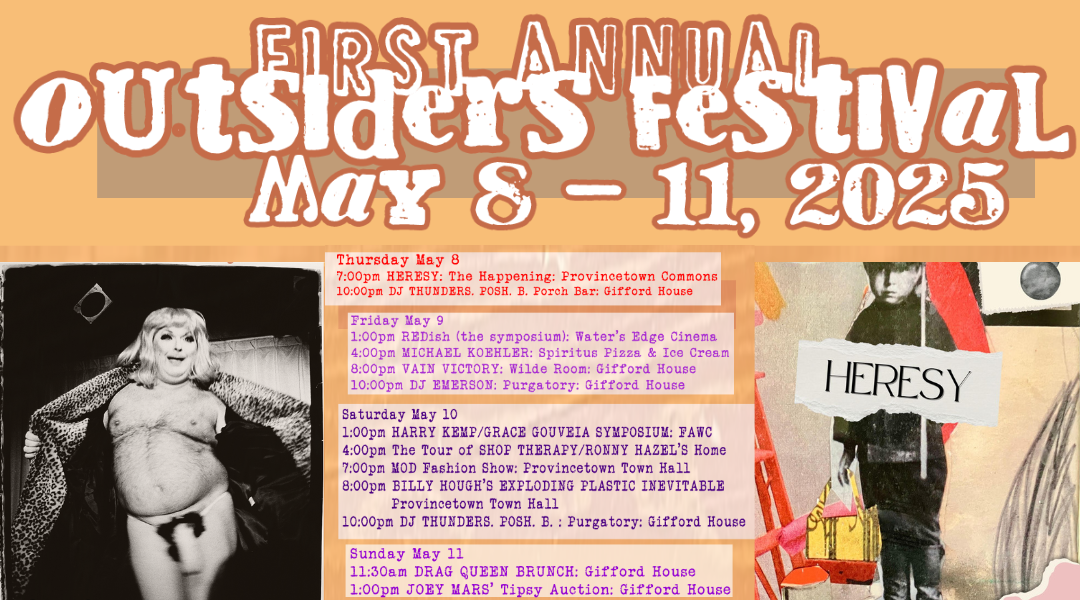

Entertainment  Events

Events  Featured

Featured  Guides

Guides  History

History  Literary stuff

Literary stuff  Most Popular

Most Popular  Provincetown News

Provincetown News  Restaurants

Restaurants  Reviews

Reviews  Shopping

Shopping  Theatre

Theatre  Uncategorized

Uncategorized  Weed

Weed