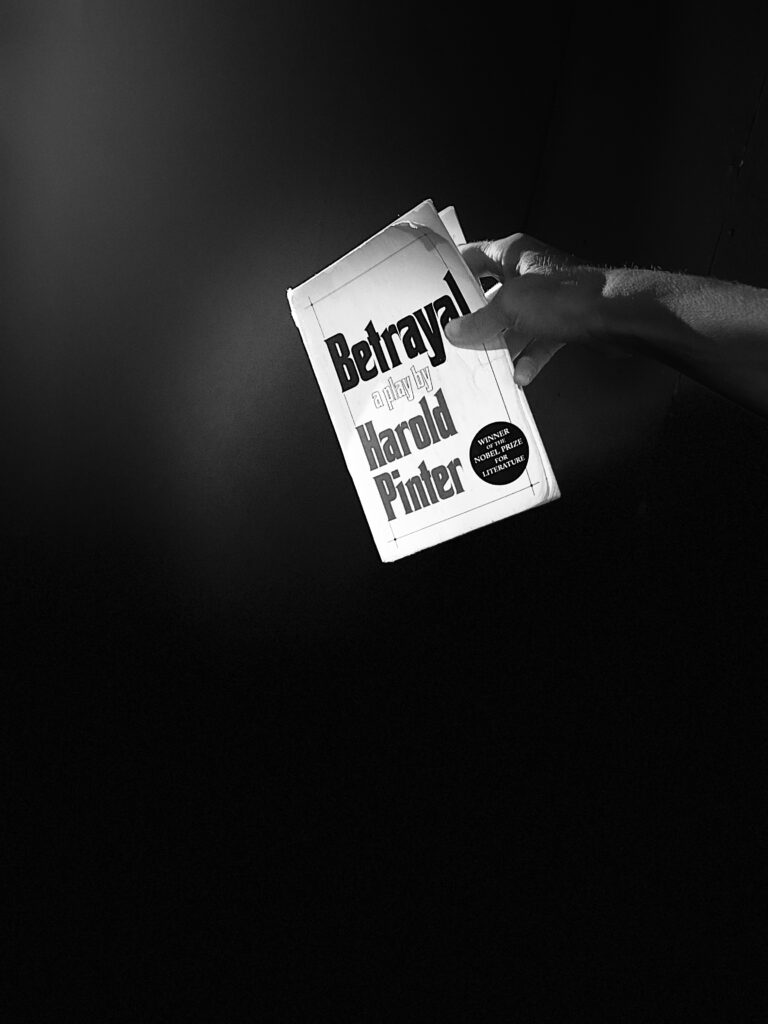

Betrayed Again! Pinter at the Harbor Stage Company

It was tempting to think, “Oh, I saw this last year already, I know what to expect from Betrayal.” And indeed last fall, the play was staged at the Wellfleet Harbor Actors Theater as an inaugural co-production between WHAT and the Harbor Stage Company. But this summer’s experience of the story is remarkably different, despite having the same director (Robert Kropf) and the same set of actors onstage.

It takes a remarkable production to pull that off.

Betrayal is the revelation of an extramarital affair told in reverse chronological order, allowing the audience’s sympathy to shift from one scene to the next and showing how meaning can change over time. The story opens with Emma (Brenda Withers) and Jerry (Jonathan Fielding) meeting in a pub two years after their seven-year affair has burnt itself out. They both have families and careers: Emma runs an art gallery, and Jerry is a literary agent whose wife knows nothing about his long extramarital relationship; Emma’s husband—and Jerry’s best friend—Robert (William Zielinski) is a successful publisher. The three have been enmeshed in each other’s lives for over a decade, and yet throughout Betrayal’s nine scenes, each attempts indifference to the fundamental questions around their relationships while—clearly—feeling them passionately.

Pinter is tricky. His often-stilted dialogue is difficult to do well; it’s bubbling with subterranean energy, but it’s the director and the actors who have to bring that energy to the fore, and these people are good. They were good before, in the vastness of the Julie Harris stage at WHAT; but they’re remarkable in the more intimate setting of the Harbor Stage. And oddly enough it’s that very intimacy that underlines the bleakness of their lives—when Emma and Jerry meet, the inevitable question, “how are you?” is answered by a helpless, “what does it matter?”

Yet as the play unfolds, Withers, Fielding, and Zielinski make the audience feel that it does, in fact, matter. Each character brings their own flawed memory and confused emotions to the scenes, each seemingly trying to figure out how something they’d thought they controlled was never what it seemed. Pinter trusts actors, and leaves them with decisions about what to choose and stress in every sentence; and Kropf and company get it picture-perfect correct here.

It’s not just memory that weaves itself through the years and the conversations, but also the question of honesty. It’s only after his reunion with Emma that a frantic Jerry learns for the first time that Robert knew already about their liaison; Robert has never spoken of it to Jerry, and that withholding of a crucial truth seems somehow as destructive as the event itself.

Pinter told the New York Times back in 1979 that “the play is about a nine-year relationship between two men who are best friends,” and while Withers’ posh Emma seems to think she’s at the center of it all, Fielding and Zielinski make it clear how much she isn’t. Emma stands on the outside of the two men whose lives and loves she’s orchestrating; their friendship, even though marred by sexual and romantic betrayal, comes though as fresh and important and honest.

Fielding’s Jerry manages to be both dynamic and restrained, his pleasure in his affair with Emma less memorable to him than his years of friendship with Robert; he is more cautious and concerned about Robert’s feelings in ways he doesn’t show with Emma. Fielding leaves us in no doubt as to which he perceives as his primary relationship.

Of course, it has to be said that Fielding and Withers are both consistently compelling in every role they undertake; the revelation for me, this time around, was Zielinski: Robert’s pain, particularly in the hotel room in Italy when Emma reveals her infidelity, emanates in palpable waves from him. He is less assured in this smaller stage space, more tentative, and it just works. My heart ached for him.

What is worth noting is the absence of scenic detail: Christopher Ostrom’s original design worked well in the vastness of the Julie Harris stage, but it is even more stark and unforgiving in the intimacy of the Harbor Stage one. Here it consists of a sliding ladder and a couple of chairs. This spare design (and the various ways in which the ladder can come between characters, enabling confrontation and cooperation alike) keeps the audience laser-focused on the characters, the distances between and among them. The empty stage also lends a certain universality to clearly affluent people; here all the wealth is stripped down, and all they have is themselves.

And that design is especially fitting for a story where love, rather than burning hot and passionate, has become icy-cold, clinical, detached.

If one were to read a synopsis of the play, it would come off as a sort of soap opera, and some productions frankly don’t allow it to rise much above that. The Harbor Stage Company, however, elevates the play so the drama is real and experienced and internalized. The audience never forgets how much these people are hurting, and what price they’re paying for their choices.

Brilliant, striking, and dazzling, this production cuts right to the painful heart of life.

Review by Jeannette de Beauvoir

Photos by Joe Kenehan

Betrayal is at the Harbor Stage Company until July 6

harborstage.org

More Recent Provincetown News

Accommodations

Accommodations  Art

Art  Bars

Bars  Books

Books  Entertainment

Entertainment  Events

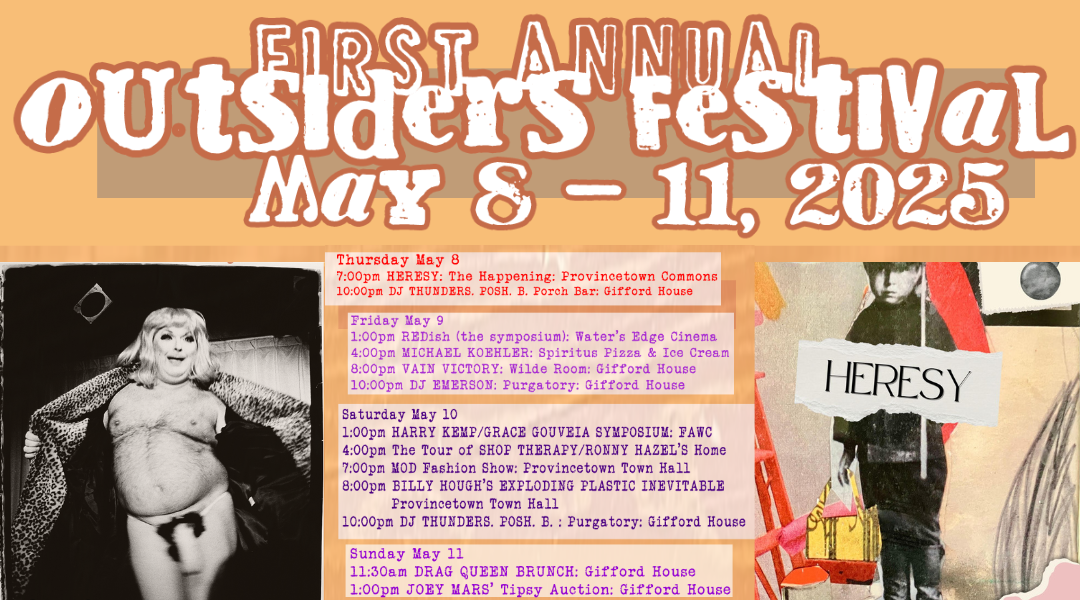

Events  Featured

Featured  Guides

Guides  History

History  Literary stuff

Literary stuff  Most Popular

Most Popular  Provincetown News

Provincetown News  Restaurants

Restaurants  Reviews

Reviews  Shopping

Shopping  Theatre

Theatre  Uncategorized

Uncategorized  Weed

Weed