Rising to the Moment: Lesbians and the AIDS Epidemic in Ptown

“Something good did come out of something terrible,” says Jackie Kelly, thinking back to the effects of the AIDS epidemic on Provincetown. “Before it happened, we were two separate communities, gay men and lesbians. What it did was make us become one.”

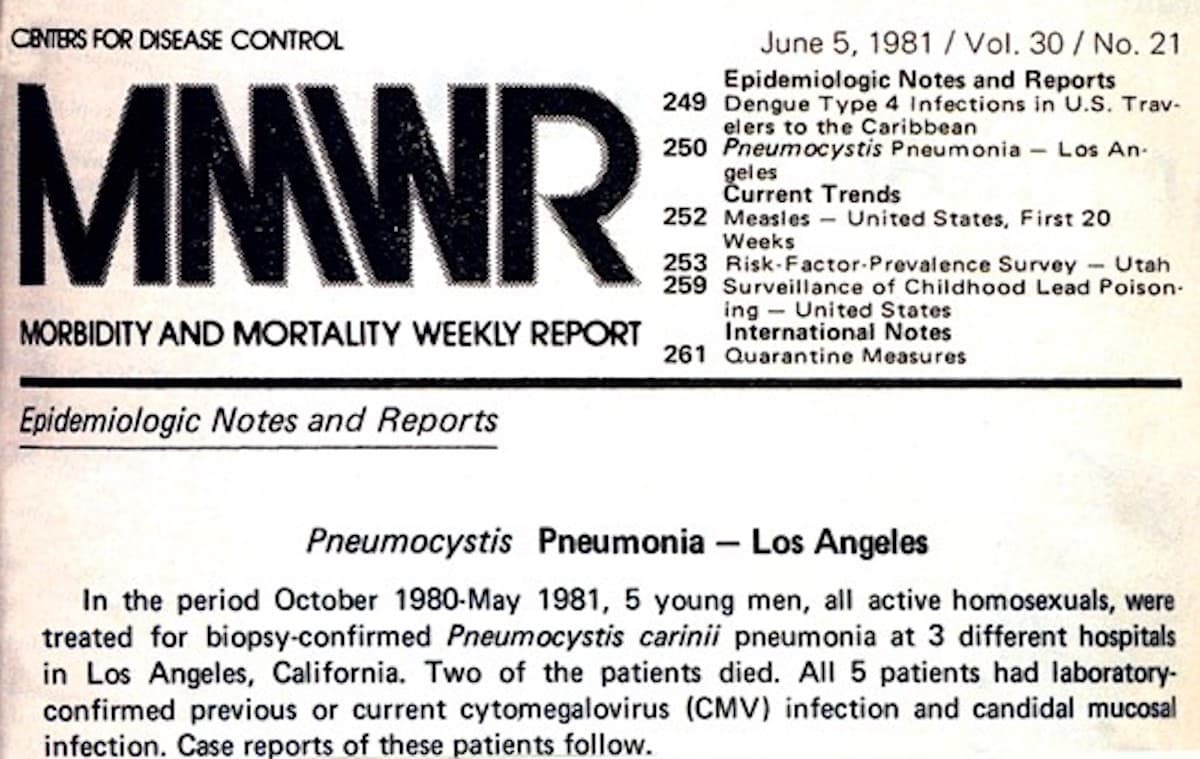

As has often historically been the case, community grew out of tragedy. On June 5, 1981, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report noted a peculiar cluster of pneumonia cases in five otherwise healthy gay men. It was the start of a time of devastation and death, of rampant homophobia and a government that turned a blind eye to its people.

In a few places, not everyone turned a blind eye. In cities like San Francisco and New York, the gay community organized, cared for each other, flexed political muscle to deal with opposition to its members desire to stay alive. Long before the epidemic, Provincetown had already been viewed by many as a safe haven, one of the few places where it was normative for gay couples to walk down the street holding hands. Once the epidemic took hold, it became seen as even more than that: a safe place to live out one’s remaining days… and a safe place to die.

In fact, for many men, Provincetown became a place one went to die. Better to live one’s last days in a nurturing community than in places and situations where one was blamed and despised for being sick. The year after that first mention by the CDC, a man drove from Colorado to Provincetown; he may have been the first AIDS patient to come here deliberately to experience the care and compassion he wasn’t accessing at home. Many more followed.

As happened in some large cities, one group that became the driving force in providing support was the women, most of them lesbians, who stepped up and cared for—and about—the gay men who were sick and dying. “The women just knew how to be nurturing,” says Jay Critchley. When in 2018 the Provincetown AIDS memorial was dedicated, Marian Roth wrote, “I came here as an artist, a lesbian with only a passing acquaintance with men. I began to meet loving men. My world began to have men in it, and then came AIDS.”

AIDS had probably come to town before it was recognized by any name; symptoms were showing up as early as 1978, but by the time significant numbers of men got sick and died, the women of the town—many of whom, like Roth, hadn’t been close to men before—did what women have done for centuries: they saw a need, and they filled it. Kelly was involved from the beginning. “My then-partner Karen Harding and I were working for Alice Foley in her café—that’s where Café Heaven is now,” Kelly remembers. “Alice was also the town nurse. We became friends, and she tapped us to help her as she was starting to recognize what was happening here. I remember Alice would deliver patients’ laundry to us late at night, and we’d spend hours running it all through with bleach. We didn’t know what else to do. Then it would get delivered back to them before morning so no one would see, no one would know whose it was.”

Doing laundry surreptitiously in the dead of night was just the beginning. Alice Foley’s presence loomed large then—and still does now, thirteen years after her death. And even today she remains a controversial figure to many.

Foley was the town’s director of public health and in 1982, along with Rose & Crown guest house owner Preston Babbit—with whom she served on the Provincetown Business Guild board—began gathering volunteers and taking care of young men who were seriously sick and dying, initially working literally out of the back of her car. It was the start of the Provincetown AIDS Support Group—one of the first in the country—but more importantly, it was the start of the creation of a more unified Provincetown community.

Brusque, uncensored, opinionated, often rude, Foley set about organizing volunteers—many of them men, but most of them women—to get trained and deliver services. Often in the beginning those volunteers were ostracized almost as much as the victims themselves. “There was lots of fear,” Kelly says. “No one knew at first how it was passed on.”

“I had to pay attention to where I was going,” Foley said when interviewed for the 2014 documentary Safe Harbor: Provincetown in the Age of AIDS. “I’d park my car up the block or around the corner, because everybody would be guessing who I was going to see. It just confirmed for me how scared everyone was.”

Fear gripped the town. “No one understood it,” says one woman living here at the time. “People crossed to the other side of the street. They were afraid you could get AIDS by touching an infected person. And then there we were, touching these very sick men, these dying men, and we weren’t getting sick. I think that helped send a message.” Kelly says, “We went out at night, in the darkness, to take care of men who were bedridden.” Jay Critchley worked for the Portuguese Princess whale watch at the time. “People would call from Boston to make reservations,” he says, “but they’d ask, ‘Are there gay people there?’

Rick Miller had just set up a psychotherapy practice in town; he’d come from Boston where he’d been working with AIDS healthcare providers at the Fenway, and Scott Penn, the executive director if the Outer Cape Health Services, hired him to do something similar in Provincetown. “The women here made themselves available to all these men that died, and they did it in a way that was powerful and profound,” he says. “The women did the bulk of the work. There were more of them, but really it was because they had a heart, they extended themselves in a way that men have not historically done for women.”

(To be fair, Irene Rabinowitz adds that “in 1995, when I became director of Helping Our Women, many guys came forward to volunteer because they wanted to give back to women who were sick, on behalf of those women who came forward when so many men in our community were ill.”)

Meanwhile the “bulk of the work” Miller refers to was intense. “The women stepped up,” says Critchley. “Every client had people helping them. No one was left alone. Everyone did what they could do; everyone did something.” It included everything and anything that was needed, often at short notice and with few resources: shopping, meal preparation and delivery, laundry, long drives to medical appointments, formal and informal counseling, health-aide work (bathing, turning patients in their beds, changing soiled linens, helping with movement), and—perhaps the most difficult of all—simply “being there” with and for a dying man.

And yet that may have been the greatest gift given. “No one should die alone,” says one woman who helped in the crisis. “What was important to me,” said volunteer Maggie Bartlett in the 2014 documentary, “was that one-on-one, that closeness, and through the night you’d be there and knowing that someone else would be coming in… just that coverage felt really good. That nobody was ever going to be by themselves at that point in their lives.”

“It was so hard for the caregivers,” says Miller. “The healthcare professionals at Outer Cape Health gave all of themselves. Most of them were women. Lucinda Worthington was a counselor, she was the one men talked to when they got their test results. She was this really WASP-y woman, not the sort you’d think you could talk to about your sex life, but she was open and liberal and she impacted the lives of a lot of men.”

He doesn’t remember there being a lot of male mental-health clinicians at OCHS, but remains impressed with the women. “Rena Bluauer helped a lot of men who were sick and dying… she went out of her way to be there in the dying process,” he says. “Everyone stepped away from professional boundaries and did whatever they could to make it more tolerable. There were three nurses there in particular: Kathy Staff, Susan Stinson, and Kristen Schanz. They all loved in this town and the people they were working with were friends and peers. They had hearts of gold. And it wasn’t just medical care—they were giving all of themselves to the men, giving the men a maternal experience many of them weren’t getting from their families. And they did it without thinking, without even knowing it’s what they were doing.”

Donna Flax agrees. “The efforts of the women caregivers was heroic,” she says. “And they did their best to empower the men they were caring for.“

Another rallying-point for the community was the Unitarian Universalist Meeting House and its lesbian minister. Prior to the ‘80s, the congregation was small—one person estimated it at about 10 people—when in 1985 Kim Crawford Harvie was called to the pulpit. Practically overnight the congregation blossomed into standing-room only. When other churches did not step up to the moment, Harvie made sure the UU did, and that connection blossomed into another connection between communities. “I don’t know what I would have done if I’d had to deal with the fear of G*d that so undid my colleagues of other faith traditions,” Harvie writes. “When I was serving in Provincetown, the parish priest had a young man living with him—his lover. But he invoked his god’s wrath at any variation on Adam and Eve, preached vividly about the eternal fires of hell, and refused to perform the funeral of anyone who had died with AIDS. I should add that neither, by the way, would he welcome to his pews anyone who was divorced. When, in my first days in Provincetown, a fishing boat sank with four divorced men on board, the families came to me to ask me to perform the memorial service. And so the queer community as well as Portuguese families began to attend the Meeting House. And then the queer children of those Portuguese families came home, and there was peace once again.”

Harvie, who later performed the first legal same-sex marriage in the United States, was one of myriad women in town who stepped up to the moment. She and Foley might have been among the most visible, but it is truly impossible to name everyone who in those years put her own life aside to be the presence, the humanity, at a time when both were conspicuously lacking in the rest of the country.

“We all had such a great love for this community,” says Kelly. “It didn’t matter that we were women or they were men. There was a sense of this happening to all of us, even though by then the mechanism had been understood. It was an assault on our community. And we had such love for these people who had come here because it was a safe place. Many of them had no family, and we became their family. We went to the wakes, and you’d see parents in total shock because of the exotic nature of the people who would be there, the shock of realizing what their son had been through.” She takes a deep breath. “We had to shield ourselves so we could take care of others. We had to build up this shield. Our grief was in private.”

Trauma and grief had almost in their own right become characters in the story. “There was so much suffering,” says Flax. “They weren’t easy deaths, people with lesions all over who were struggling to breathe. And you have to remember… they were all so young.”

“This was much more intense than what I’d experienced in Boston,” says Miller. “People who live in Provincetown have a reason to live here. Whether they’re actually artists or not, they have a reason to live life more intensely. So the stories I was hearing were so over the top, with such eccentric characters, there was a different kind of drama and flair to it. You could say that people who live here are less standard than other people. So both the care providers and the dying people were different from anywhere else.”

“There had been some services in town before,” remembers Critchley. “You have to remember, in the ‘70s, this was a hippie town. So there was the Provincetown Drop-in Center, mostly dealing with issues around drugs—pot, LSD, what have you. Alice Foley was involved with the center, but there were problems—we tried to get licensed and the process overextended us, we went bankrupt and eventually folded.”

Foley’s energy was soon absorbed by the ASG. The group trained volunteers, made appointments, provided resources, and did things no one else in the country was doing, including providing 24-hour care to patients with AIDS-related dementia. In the 2014 documentary, Mary Chatlos spoke of a young man “who was a great intellect but developed dementia. I was terrified.” She didn’t want to see this person whose mind she so admired deteriorate. “But I went and took care of Victor, and he was a lamb.” The general consensus of volunteers was that what they were doing, with even these most difficult patients, was never a duty, only a privilege.

“Alice was a wonderfully imperfect person who was one of the first people—one of the first nurses—in the world to take on the AIDS epidemic with her sleeves literally rolled up,” wrote Richard Ferri. “She got her hands dirty when most people were fearful of touching someone with AIDS.”

There were different approaches embraced by different community members. “I started going to Healing Arts workshops, also known as Hearts workshops,” remembers Dianne Kopser. “They were held at the UU. Different facilitators would lead each session and share wisdom in their areas of expertise. So, there were talks about meditation, visualization, diet, crystals, all kinds of things, some of them oddball, many of them very helpful. I learned a lot. The atmosphere was supportive and loving. Some of the founders of the AIDS Support Group played key roles there.”

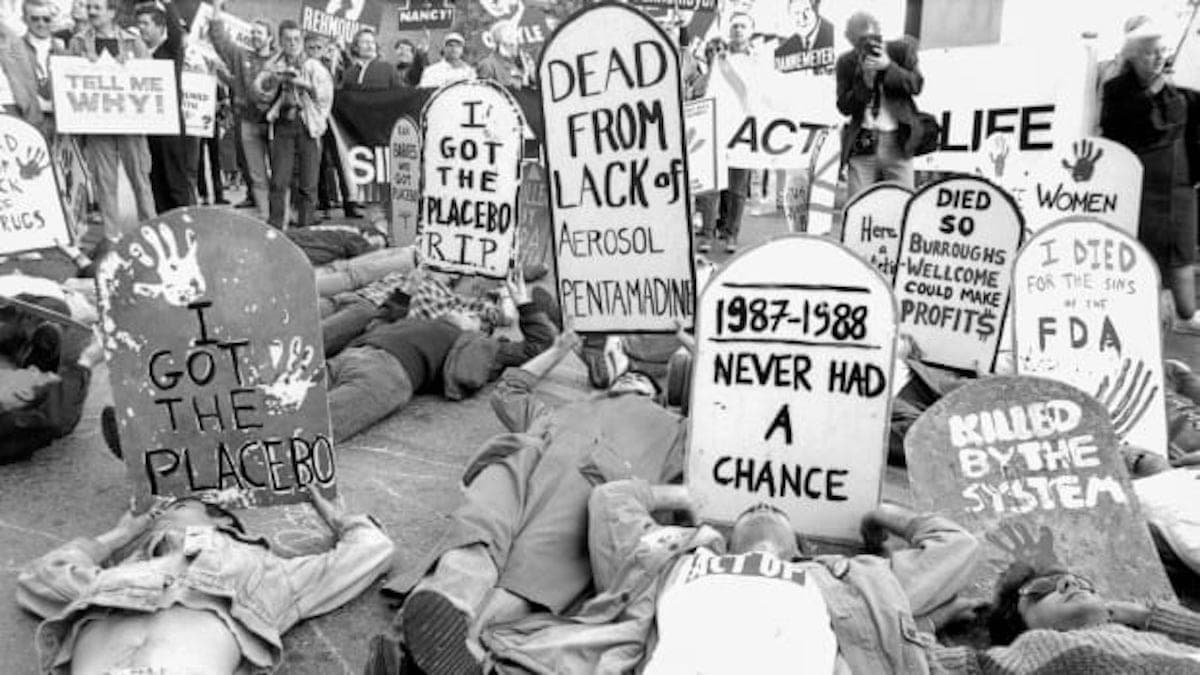

If there was a rift in the community, it wasn’t along gender or sexuality lines, but rather between trust in traditional versus alternate therapies. In 1984 another group emerged, Positive People With AIDS, which rejected the medical model of treatment. “The FDA was doing nothing,” Critchley says. “So people thought they should learn how to take care of themselves. The PWA coalition was all about self-empowerment.” Louise Hay had become a figure on the national stage and she served as an inspiration. “There were lots of approaches,” says Kelly. “The PWA was a growing coalition that focused on alternative treatments.” But Foley had only to see a small but growing library of self-help and alternative-healing books appearing at the ASG office to go ballistic; the medical model, for her, was the only way forward. “That movement pushed the clinics to do more,” says Catherine Russo, director of the 2014 documentary. “People found their voice with Act Up.” But it did so at a cost, and the “die-in” staged at the Outer Cape Health Services pitted the two groups dramatically—and, for many, hurtfully—against each other. Then-executive director Scott Penn remembers that moment with sadness, recalling how incredibly distressing the action was for healthcare providers already doing their best, giving above and beyond.

Foley had no problem taking on controversy. While many remember her as abrasive, for others she was a true friend. “She was my mentor when I first joined the Provincetown AIDS Support Group in the early ’80s,” Ruth Gilbert remembered, “and she told me in no uncertain terms that, yes, I could drive the van to Boston and, yes, I could take care of sick people with no nursing skills—and I damn well better. And I did.”

Driving to Boston was an exhausting business. Patients had to be picked up at 4:30 or 5:00 in the morning to make it to all the appointments. It had been made clear to the community that Cape Cod Hospital was not an option, and initially only two hospitals in Boston—Mass General and Deaconess—would even see patients with AIDS. The ASG managed to buy a van, so men would be collected at their various homes, the van would go to Boston and take each of them to his separate appointment, then collect them all and do the two-and-a-half-hour drive back, a grueling schedule.

The hospitals were unpleasant at best and frightening at worst, and when inpatient care was called for, there were other problems. In the 2014 documentary, Jackie Freitas recalls, “if they were in the hospital I would stay with their animals so they wouldn’t have that to worry about them. That was a big thing for me, and it was a big thing for them, to know they were being taken care of by someone who really cared for them.”

Foley was tireless. She’d get a call for help at 4:00 and by 4:30 would have a volunteer on-site and a care schedule in the works. Bartlett remembered “Alice’s force and her very directness—she didn’t mince words and we had a lot to do and it seemed that that’s the reason you were there and she—it felt to me as if she managed it in a way that I can’t picture anybody else managing at that time because she was everywhere. She’d be picking up parents who were coming to see their son, after not having seen him for a long time and be with him when he died. She would get a place for them to live and she’d give them dinner. She was an amazing force, that’s what I was impressed with.”

“Alice was a force,” Miller agrees. “She worked nine million hours. She got so much to happen, but also at the expense of sparing no-one’s feelings. She was so abrupt, and so angry.”

Rabinowitz went from being a volunteer to being a case manager to being housing program director for the ASG. “I thought that there was a piece missing and what it was, was housing,” she said in the 2014 documentary. “I asked Alice if I could look into creating housing and work with the housing authority to find a piece of property. She said go for it.” Rabinowitz did, and “developed Foley House, collaborating with the Mass Department of Public Health and the Provincetown Housing Authority. We had a team of people with AIDS helping with design (Pasquale Natale, Mark Bulman, and Jim Rann). Our architect, Phil Lindquist, was a partner in this and approached it with understanding, listening to the concerns put forth. I was involved, as was Alice, through the groundbreaking in 1996.”

“This house is proof that we are family here in Provincetown,” said Foley at that groundbreaking. Foley House was at that time the only such place on the Cape: an assisted-living, congregate home for otherwise homeless people living with AIDS.

There’s Irene, very strong, and Bill. Those are the ones that really stand out in my mind that held it together and it just felt very crucial to be a part of the town and to be with that group. It felt very ecumenical whenever you would go to a service with somebody, for one of the clients who died, you know the whole town would show up for it. So it was definitely a community sense that I have never felt to this extent anywhere.”

“Women were integral in the founding and implementation [of the ASG],” says Rabinowitz. “Alice and Preston were visionaries and created something that stands to this day. Three of the four first employees were women: Sandy LaRoe, me, and Sam Demarest. Alice, of course, was our executive director. Many of the volunteers were women who took on the role of what was then called a “buddy” to someone with AIDS who had no or limited family. There are many, many names, so I don’t want to name people without being thorough. They often went over and beyond the basic duties and became the person who held it together for those who were sick.” It is in fact impossible to name all the women who volunteered their time, their energy, their funds. Pat Shultz and Lenore Ross, patrons of the OCHS, were vital in the work. So were many other nameless faces who have since died, moved away, tragically been forgotten.

“Women in town stepped up to the plate in a way that was amazing and beautiful and remarkable,” remembers Miller. “There really was unity and cohesion for the first time.” He pauses. “It didn’t last,” he adds. “The class stuff wasn’t as profound as it is now,” agrees Flax. “Issues of class were less visible and less divisive at that time. It just felt like a simpler time.”

The condo conversions—greeted eagerly by the community in the ‘80s as providing an option for homeownership to people who couldn’t afford a whole house—paved the way for the Provincetown of today, still quirky, still caring, but much wealthier and with possibly even more profound divisions. When the pandemic arrived in 2020, there was a stirring of a memory of the earlier plague, as volunteers sewed facemasks and healthcare professionals handed out hand sanitizers in the same way they used to hand out condoms. But it is nonetheless different now.

Which is not to say that it couldn’t still change—again.

More Recent Provincetown News

Accommodations

Accommodations  Art

Art  Bars

Bars  Books

Books  Entertainment

Entertainment  Events

Events  Featured

Featured  Guides

Guides  History

History  Literary stuff

Literary stuff  Most Popular

Most Popular  Provincetown News

Provincetown News  Restaurants

Restaurants  Reviews

Reviews  Shopping

Shopping  Theatre

Theatre  Uncategorized

Uncategorized  Weed

Weed